The State of Play of UK Fusion

If we solve fusion, we solve for meeting a large portion of the UK’s future energy demands. Once just a distant dream of abundant clean energy, commercial fusion is advancing at speed. The UK has long been the world leader in fusion in every aspect - technical expertise, experimental breakthroughs and policy environment - but that is threatening to change. World superpowers, namely the US and China, are aiming for commercial fusion deployment in the 2030s, and with current UK ambitions, that will be sufficient to beat us. And that is a big problem.

Fusion in 60 seconds

Fusion as a mainstream technology is nascent and knowledge of what it actually means is not widespread. Fusion is the process that powers stars - smaller nuclei of atoms smash together and make larger nuclei, releasing a lot of energy in the process. The most common is hydrogen smashing together to make helium. It is the direct opposite process of nuclear fission - the process used in current nuclear plants - where heavier nuclei split apart into smaller nuclei and release energy.

On first look, this implies infinite energy - if both fusing and fissioning nuclei release energy, then we can fuse and fission in an infinite loop and live happily ever after. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Both fusion and fission cease to release energy once the reactions reach iron, as shown in the graph below. This is due to a concept called binding energy, which is fascinating but unimportant for the purpose of this blog.

Figure 1 - Graph of binding energy per nucleon plotted against atomic mass number.

Source: SchoolPhysics

Fusion has several practical benefits over fission and other renewables. Fusion offers the reliability of fission with a similarly small physical footprint. By delivering the steady output of a traditional power station with a very low lifetime emissions profile, fusion provides the ultra-dense energy needed to decarbonise heavy industry and stabilise the grid without paving over the planet.

Additionally, safety would be of far less concern in a commercial fusion plant than in a fission plant. The waste products produced in fusion are far easier to deal with than in fission. The main byproduct of fusion is the reactor vessel itself, which will remain radioactive for a matter of hundreds of years compared to the hundreds of thousands of years of fission fuel. The only chemical exhaust is helium, which can be reused. Furthermore, a runaway chain reaction (a la Chernobyl or Fukushima) is not possible in a fusion plant. Therein lies the key problem with fusion, however.

A fusion plant would involve recreating the conditions of a star, among the most extreme in the universe, on Earth. This requires immense amounts of energy input. Net energy gain from fusion reactions has only been achieved a handful of times, and at nowhere near the scale that would be required for a commercial plant.

Two routes to Earthly fusion

There are two routes to achieving fusion on Earth: Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF) and Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF).

MCF tries to hold a super-hot plasma in place using magnets. Tokamaks are the best known example, and they’re where the UK has built most of its expertise. The big engineering challenge here is sustaining a stable plasma, continuously, inside a complex machine that has to handle huge heat loads and neutron damage.

ICF is conceptually simpler. Instead of holding plasma steady, you compress a tiny fuel target very fast so it fuses before it can fly apart. The core engineering challenge for ICF is turning individual shots into something suitable for constant energy output: cheap targets, high repetition rates, and drivers you can run all day.

Both approaches are seen as scientifically credible in the fusion space. Most governments are pursuing both technologies equally. There is, however, one significant outlier: the UK.

Fusion policy in the UK

The centrepiece of UK fusion policy is the UK Fusion Strategy, with a clear political objective: build a prototype fusion plant by 2040 and grow a domestic industry that can export technology into a global market. The flagship project is STEP, a spherical tokamak, so firmly in the MCF camp.

The government is backing this ambition with money. In January 2025, the government announced £410 million for fusion R&D in 2025/26 through the Fusion Futures Programme. Then they committed over £2.5 billion across five years to push STEP towards delivery. This level of capital investment signals to industry and investors that fusion is being taken seriously.

Regulation is also moving in the right direction. The UK has decided to regulate fusion separately from nuclear fission, and it’s finalising a Fusion Energy National Policy Statement (EN-8). This kind of clarity matters. Investors will tolerate technical risk; they are more cautious of policy and planning risk.

The problem is that the government's practical interpretation of fusion is still basically just tokamaks - the massive, doughnut-shaped machines that are used in STEP and MCF experiments.

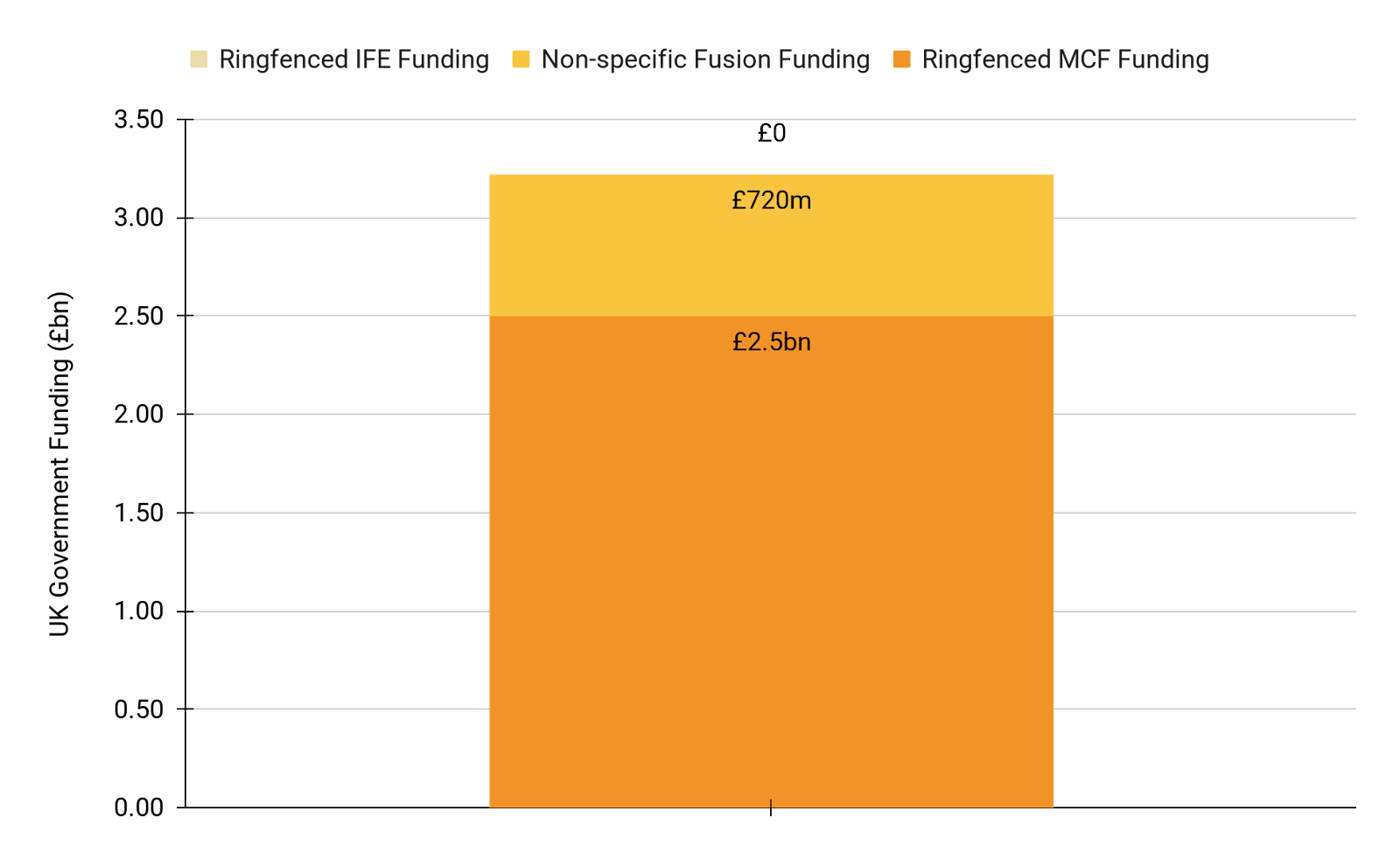

Figure 2 - STEP funding dominates the fusion space in the UK.

Nearly all public funding lines run through STEP and MCF. STEP has been allocated £2.5bn, while the only routes that could even potentially fund ICF projects are parts of the Fusion Futures Programme and Starmaker One, but even this is not ringfenced. The government acknowledges multiple approaches in its strategy and planning documents, but there is no ICF equivalent of STEP - no national inertial programme, no dedicated capital, and no mechanism to take ICF from the lab to the grid.

Why does this matter?

ICF might be the route through which the first fusion plant is realised. It has reached milestones MCF has not. The US National Ignition Facility has repeatedly achieved net gain. MCF, by contrast, has not crossed scientific breakeven (meaning getting more energy out than you put in).

Fusion is moving into a first-mover industrial phase: the countries that help a technology mature earliest write the standards, own the supply chains, and become the default export partner when other nations decide they want plants. ICF supply chains are being built now, and they will not wait for UK policy to catch up.

The export opportunity is big. The development of an ICF reactor will yield a unique set of tradable technologies. Furthermore, the export of knowledge, which the UK already has in abundance, will be another valuable commodity that the UK will lose out on if we allow the US and China to beat us to the line.

STEP is aiming for an operational prototype by 2040. Helion Energy in the US has signed a power purchase agreement with Microsoft to supply fusion electricity as early as 2028. China’s BEST reactor is slated for completion in 2027, with the goal of demonstrating fusion electricity generation shortly thereafter. By running these advanced pilot programs in parallel with rapid industrial scaling, both nations are positioning themselves to achieve commercial fusion power well before the UK's plant comes online.

Fusion offers a pathway to a British industrial renaissance. By colocating fusion plants with industrial clusters, the UK can decarbonise its heaviest industries without de-industrialising its economy. While the upfront cost of building these machines is high, the long-term economics are transformative. Instead of paying for imported fuel forever, we pay for the technology once, securing cheap, clean energy for generations.

In short, there are two accepted routes to commercial fusion, but the UK is, inexplicably, disproportionately favouring one of them. As the industry moves into the first-mover stage, if the UK doesn’t place more emphasis on ICF, we may well end up losing our position as fusion world leader and with it a wealth of export and influencing opportunities.