Better politics starts with conversations only few are having

Written by Jule Kegel

When asked about their views on politicians, the British public does not hold back. Eight in ten Britons agree that the gap between ordinary people and politicians is wider than the differences among ordinary people. The same proportion say that MPs in Parliament quickly lose touch with the public, and as many as 83% agree that politicians talk too much and take too little action. The public is also largely skeptical about their ability to influence actual political decisions, with 73% agreeing that people like them have no influence on what the government does.

In an ideal world, politicians are meant to come from among ordinary people and represent their views. So why is their image so poor that many do not see them as “one of us” or responsive to people’s needs? Part of the reason may be that politicians and the public do not interact frequently enough.

Our polling shows that overall, only 31% of the public have ever spoken to a politician. A further 17% have seen a politician in person without speaking to them. This means that half of all Brits have never even seen a politician in person!

People who have closer contact with politicians tend to show much lower levels of negative attitudes. Among those who have never had any contact, 25% express very strong anti-elite sentiments, understood here as the average level of agreement with the four statements described above. This share falls to 21% among people who have at least seen or spoken with a politician, and drops further to 10% among those who count a politician in their wider or close personal circles.

At the same time, closer contact with politicians coincided with a drop in anti-elite values. Among those with no personal contact, 41% belong to the group with the lowest levels of anti-elitism. The figure rises to 62% among those who have a politician in their wider circle and to about 67% among those who have one in their close circle.

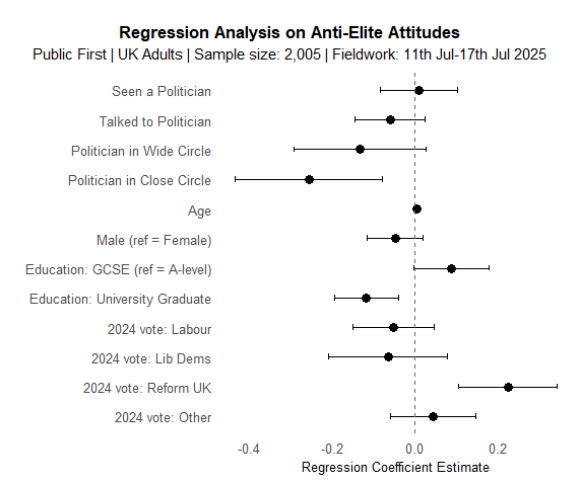

When we run a regression analysis and control for personal characteristics such as age, gender, education, and 2024 vote choice, only having a politician in one’s close circle remains significantly associated with lower anti-elite attitudes. The analysis also reveals some broader patterns, such as university graduates being less anti-elitist than people with A-levels, and Reform voters being more anti-elitist than Conservative voters.

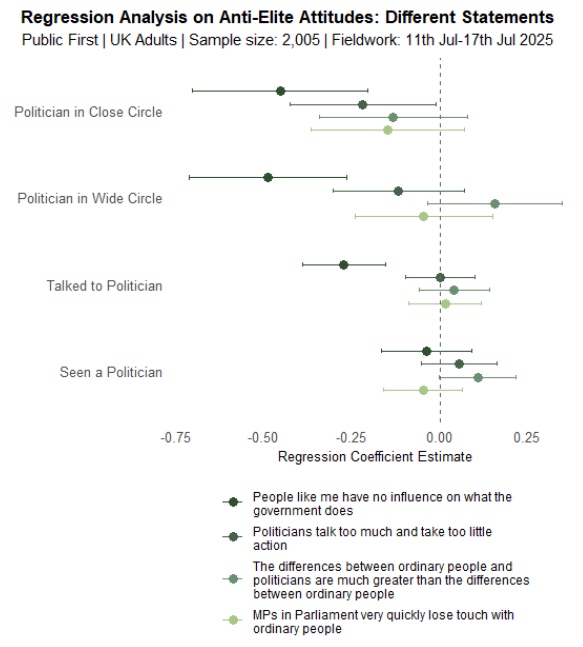

Breaking anti-elitism down into its different components shows an interesting pattern. There is no statistically significant link between contact with politicians and agreement with the statements “MPs in Parliament very quickly lose touch with ordinary people” and “The differences between ordinary people and politicians are much greater than the differences between ordinary people.” Agreement with the statement “Politicians talk too much and take too little action” is only significantly lower among those who have a close personal relationship with a politician. By contrast, agreement with the statement “People like me have no influence on what the government does” is lower across all groups who have at least spoken with a politician.

This suggests that encounters with politicians may not change people’s overall image of politicians but instead affect how much influence they believe they themselves can have in politics: in other words, their sense of political efficacy.

While this poll cannot reveal the exact reasons why some people have contact with politicians and others do not, it suggests that lack of contact is not necessarily due to a lack of interest. Overall, 49% of respondents would like politicians to engage with them more, with the highest desire among those with limited contact: 47% of those with no contact, 49% of those who have only seen a politician, and 57% of those who have spoken to one. At the same time, only 5% of respondents want politicians to engage with them less.

To sum up, Britons may not necessarily develop a more positive image of politicians simply through personal contact. What such contact does achieve, however, is a stronger sense that one’s voice is heard. This is important for democracy, as greater political efficacy encourages participation and helps sustain a healthy connection between citizens and politics. Politicians should therefore reflect carefully on which groups they attempt to engage with. This is all the more pressing given that many citizens actively want more engagement, not less. Citizens, in turn, can help close the gap by making use of the opportunities to connect provided by their representatives.