A Cynical Mandate: Why Labour’s Real Problem Is Anti-Politics

Context

Public First has been researching anti-political attitudes since before the 2024 General Election. This work emerged from qualitative research that made it increasingly clear how difficult it had become to engage the public in conversations about policy. When asked what they wanted to see from the government, people often replied with vague but telling phrases: “anything at all”, or “just actions rather than words.”

It became evident that the term “anti-politics” was being used to describe a wide variety of attitudes — from voter disengagement to frustration with political institutions. Using a data-driven approach, we developed a framework that breaks “anti-politics” into three distinct traits:

Cynicism - a widespread (45% of the public express this trait highly) cynicism about the political system. Belief that politicians are out of touch, and only look out for themselves.

Dissociation - a more acute belief that political parties are basically the same, that their vote does not make a difference. However, this group is very politically active.

Powerlessness - a disengagement and disinterest in the political system. Less likely to feel represented, and less likely to vote or encourage others to vote.

Each of these traits is measurable and widely shared across the electorate. Powerlessness and dissociation are more common among younger voters and graduates, while cynicism is more pronounced among older respondents. Issues like healthcare and immigration are more frequently prioritized by cynical voters compared to those who score low on this trait.

A Cynical Mandate

Labour came into power on the back of a large number of cynical voters. This is why our definitional ambiguity around antipolitics matters so much; if you just view antipolitical people as those who don’t vote, or who vote independent, you miss the widespread antipolitical sentiment among Labour’s voting base itself. And there are reasons Labour should worry. Around 30% of its 2024 voters fall into the highest category of cynicism — scoring 6 or 7 out of 7 on our scale.

Since the election, support among these voters has sharply declined. In October 2024, 58% of highly cynical Labour voters said they would vote Labour again. By June 2025, that figure had dropped to 35%. During the same period, support for Reform UK among highly cynical voters has jumped to 34%, making it the clear frontrunner in this group. Labour, by contrast, has fallen to just 9%.

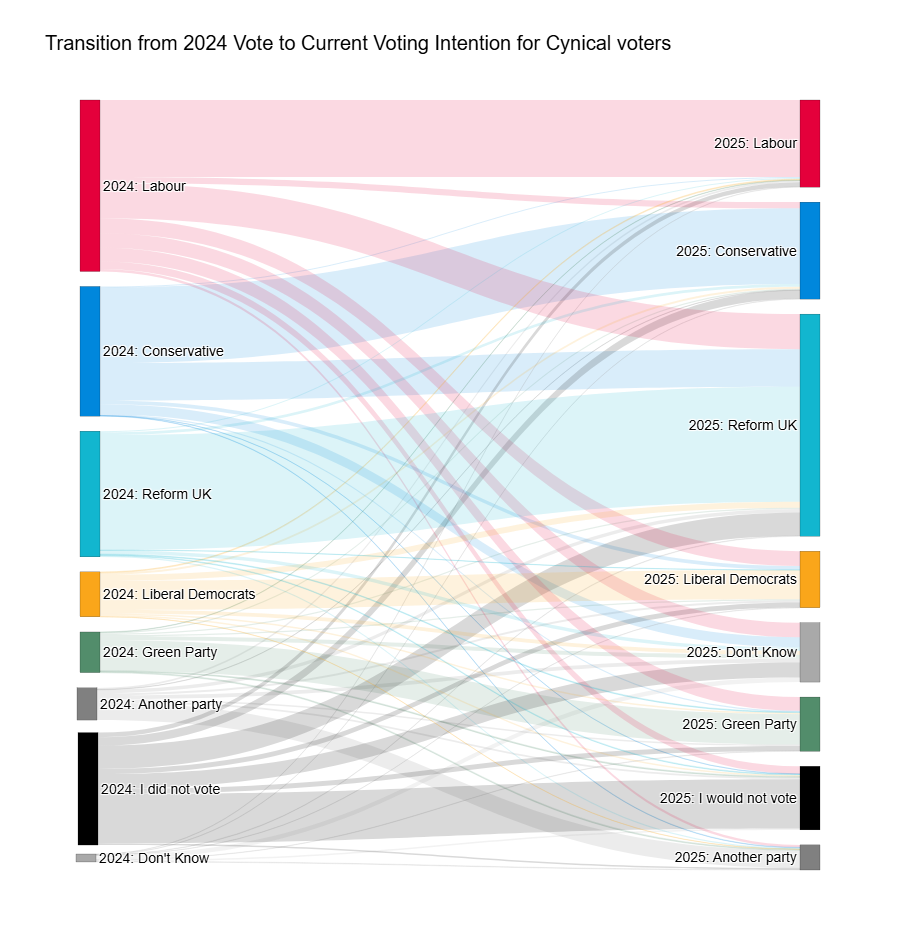

This dynamic is more clearly visualised in the chart below, which tracks how cynical voters have moved since the 2024 election:

Note: Data reflects views of respondents with high political cynicism, defined as scoring above 6 (out of 7) on a composite agreement score across three statements: "Politicians only look out for themselves"; "Most political discussions are just talk with no real action"; "It doesn’t matter what the public thinks because politicians will do what they want anyway". Responses were on a 7-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). This group makes up around 42% of the original sample.

Reform’s gains are not limited to its 2024 base — it is pulling support from across the spectrum, including cynical voters who previously backed Labour, the Conservatives, or did not vote in the last general election.

Over 70% of highly cynical voters now hold an unfavourable view of Labour — significantly higher than the national average. While other parties also face criticism (Lib Dems at 42%, Reform UK at 40%, and Conservatives at 55%), Labour’s numbers are notably worse.

Starmer as the Focal Point of Discontent

Much of this disillusionment is focused on Keir Starmer himself. When asked to evaluate political leaders, 72% of highly cynical voters described Starmer as a bad leader, while only 10% considered him a good leader. These voters are nearly twice as likely to rate Starmer poorly than they are to say the same of Nigel Farage (38%) or Kemi Badenoch (36%).

Looking more broadly at overall favourability, highly cynical voters reserve their strongest negative views for Starmer, giving him a net favourability rating of -68 percent. Leaders like Nigel Farage, Kemi Badenoch, and Ed Davey receive a mix of positive and negative sentiment, but none match the scale of disapproval directed toward the Prime Minister. For example, the same group is split on Farage, with around four in ten having favourable and unfavourable views, resulting in a net favourability of -2 percent.

Note: Data reflects views of respondents with high political cynicism, defined as scoring above 6 (out of 7) on a composite agreement score across three statements: "Politicians only look out for themselves"; "Most political discussions are just talk with no real action"; "It doesn’t matter what the public thinks because politicians will do what they want anyway". Responses were on a 7-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). This group makes up around 42% of the original sample.

This sentiment extends to matters of trust and relatability with around 85% of high cynical voters not trusting or liking Starmer. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, public opinion on whether he kept his promises was split: 39% thought he didn’t, 32% thought he did, and 28% weren’t sure. By June 2025, a clear majority (59%) said they believed he did not keep his promises, rising to 82% among highly cynical voters.

This group does not just question his record — they question his intent. Nine in ten believe he would lie to the public if it improved his chances of winning an election. Over four in five (86%) think he tailors what he says to suit his audience. Most notably, 76% believe that if he broke a promise, it would be because he never intended to keep it, rather than because circumstances forced him to.

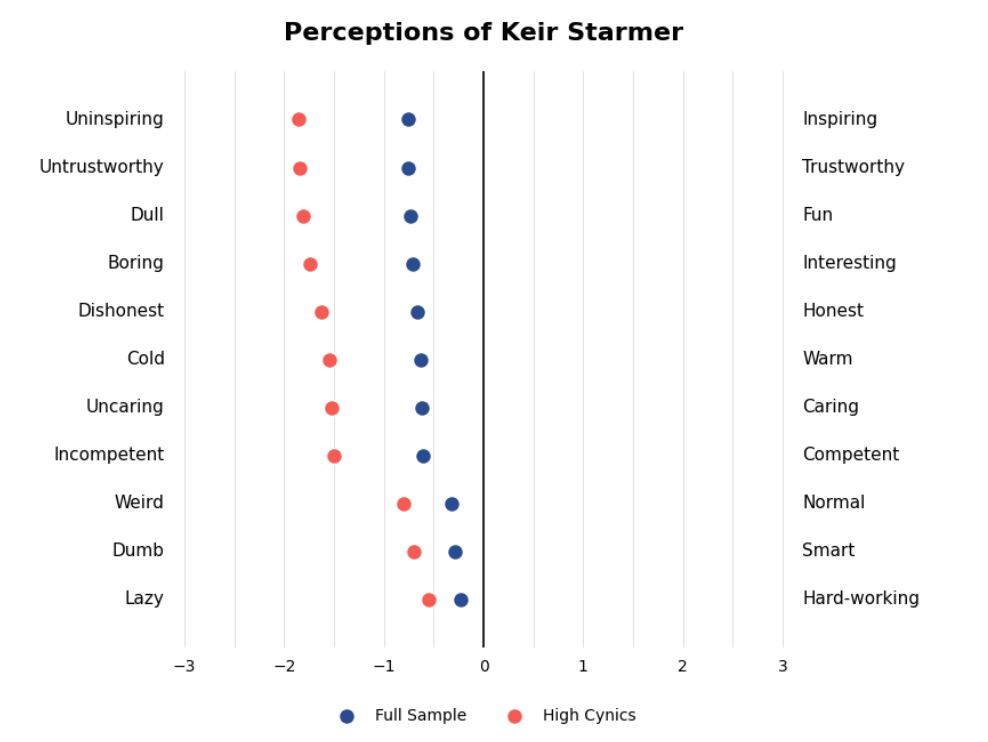

We also asked respondents to rate Starmer on a series of contrasting personality traits — such as “honest” vs. “dishonest”, “inspiring” vs. “uninspiring”, “competent” vs. “incompetent” — using a 7-point scale ranging from –3 (strongly negative) to +3 (strongly positive). The chart below shows the average rating for each pair, comparing the full sample with highly cynical voters. While the general public already leans negative, highly cynical voters are far more likely to see Starmer as untrustworthy, dishonest, uncaring, and incompetent.

Note: Each characteristic was measured on a 7-point scale from -3 to 3, where the lowest value was the negative attribute, such as incompetent, and the highest value was positive, such as competent. The values in this table represent the average score, which could range from -3 to 3 for all participants in this poll.

This shift is reinforced by a broader perception of social and cultural distance. Starmer is not simply seen as untrustworthy and incompetent but as out of touch, and fundamentally different. Nearly nine in ten highly cynical voters believe he’s never had to worry about money. As the chart below illustrates, most also think he comes from a different background, is hard to relate to, and doesn’t represent people like them.

Note: Data reflects views of respondents with high political cynicism, defined as scoring above 6 (out of 7) on a composite agreement score across three statements: "Politicians only look out for themselves"; "Most political discussions are just talk with no real action"; "It doesn’t matter what the public thinks because politicians will do what they want anyway". Responses were on a 7-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). This group makes up around 42% of the original sample.

This matters because these voters were not incidental to Labour’s win. They were a key part of the 2024 coalition — and they are now turning away. Labour’s problem is not just low satisfaction among its base. It’s the growing belief among a large and politically significant group that the party — and its leader — were never on their side to begin with.

An Identity Problem, Not Just a Personality One

Cynicism is a response to a political culture that has repeatedly failed to deliver. From the expenses scandal to Partygate, from Brexit fatigue to NHS collapse, the public has absorbed years of instability and unfulfilled promises. Starmer promised a break from that. But for many, the first year of Labour governance has felt more like continuity in a better-tailored suit.

The scale of this disillusionment suggests that the collapse in trust is not just emotional but structural. For voters who already feel the political system is failing people like them, Starmer appears to be governing in someone else’s name entirely. Most of this group think Starmer is more responsive to the views of high earners (57%), business leaders (53%), and middle-class voters (45%) than to working-class communities.

Note: Data reflects views of respondents with high political cynicism, defined as scoring above 6 (out of 7) on a composite agreement score across three statements: "Politicians only look out for themselves"; "Most political discussions are just talk with no real action"; "It doesn’t matter what the public thinks because politicians will do what they want anyway". Responses were on a 7-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). This group makes up around 42% of the original sample.

When we asked respondents what they would say to the Prime Minister if given the chance, what emerged was not just frustration about a specific policy or broken pledge, but a deeper sense of abandonment. They see a leader who is distant, unrelatable, and unwilling to stand up for the people Labour was once built to serve.

If you could address Keir Starmer directly, what would you say to him?

“Drop the title, and return the Labour party to its roots of representing the working classes, not being a lighter version of the Tories. Start representing the British people, and protect our borders.”

“I would tell him that what he has done since being elected is not what I believed he would do and I am very disappointed in home. I have always been a Labour voter but no more.”

“Resign! You have no idea of how working people live. You do not represent traditional Labour values.”

“I’ll tell him that he’s had a big chance to reset things in the UK and that the people are tired, frustrated, and losing faith in politics. It’s not just about being competent (though that’s a start), it’s about showing real vision and giving people something to believe in. Don’t just play it safe, be bold where it matters, protect the vulnerable, and actually deliver change.”

The Risk Ahead

Labour entered office on the promise that, with Keir Starmer, hope would be restored, chaos would end and Britain would start to rebuild. Twelve months on, the voters whose cynicism helped to secure that majority see little evidence that the page has really turned.

Only one in three believe Labour has made meaningful progress on any major policy goal. And crucially, most do not expect that to change. More than two-thirds does not think Keir Starmer will remain as Prime Minister up to the next General Election.

Cynical voters vote tactically, punish failure quickly and shape the national mood. If Starmer struggles to relate to its electorate and demonstrate meaningful progress, the party and its leader now risks being redefined — not as the alternative to a failing system, but as the latest iteration of it. And in a political landscape shaped by rapid cycles of disillusionment and re-alignment, that perception may prove more consequential than any single policy.

Labour’s mandate in 2024 was not just for competence — it was for renewal. Competence is a low bar in a post-chaos era, but it does not inspire or retain public allegiance. Renewal demands evidence that politics still matters, that government can still act decisively in the public interest, and that leaders can still be trusted to speak honestly about the scale of the challenge. So far, many voters — especially those most cynical — see little sign of that.

For a party elected on the promise of “turning the page,” being seen as the custodian of stagnation is not just damaging — it opens the door for others. As Starmer continues to look like ‘just another politician’, Reform UK and Nigel Farage are well positioned to capitalise on the frustration that both major parties have failed to address.